Porktrack: how I turned a goofy idea into a real career

A time gone by⌗

I’d like to tell the story of how I got into the software engineering field, but like any post I make on this website, I feel the need to justify the endeavor first. I’m sharing because whenever I’ve shared it with folks in the past, they seem to have enjoyed it and almost always ask clarifying questions in disbelief, which I think is a safe indicator that the story is maybe good. I’m also interested in simply documenting this story while the details are still immediately recallable.

To set up some context, in 2012, I took CS101 and was primarily left with a fondness for programming. I loved figuring out how to make the computer do things, and I loved finding new things to make the computer do. I kept writing trivial programs and exploring programming in my spare time even after I left school. I wrote some math quizzers, a random color generator, and some other miscellaneous things that were useful to nobody, myself included. I remember contemplating building something like a Twitter client next, but going from generating a random color to authenticating over OAuth when you don’t understand how websites work is a daunting task.

I was working as a security guard for a local condominium complex. I made $11 an hour, and I had just gotten married. I remember sitting next to my new bride, in awe of the responsibility that she had entrusted me by marrying me, and feeling wholly unworthy of the privilege. I was, in colloquial terms, a scrub, but I was at least a self-aware scrub. I wanted a way to turn my fondness of programming into a career, so as to rectify my scrub stature.

What to build⌗

The thing that is hardest about learning how to write code is knowing what to work on. You can be the best and brightest student our planet has ever known, and you could spend hours absorbing the knowledge of how conditionals work, where and when to attach a method to a class, etc., but if you don’t know to what end it’s for, you will never apply it meaningfully, and your understanding will dwindle. I recognized this problem early on and sort of just dealt with it by coming up with (and getting myself hyped about) contrived applications to build. I was never really motivated by games programming either, which is not to cast aspersions at anybody, just a note that I didn’t have an interest in that vehicle for developing programming skills.

Seeking guidance⌗

Thankfully, the building I worked at had lots of software engineers as tenants, and I was their middleman to receiving their packages. One day, I asked a resident for guidance around what I should build next. He responded by suggesting I create a website, which I initially rejected categorically. “I don’t want to be a web developer!” I whined. Web developers, I’d surmised, spent their days changing div colors and filling websites with ads. I wanted to do Real Programming™. “The web is dumb! I want to be a Real Programmer™!” I whined further. What he said next was a pivotal moment for me:

"The web's not dumb, you're dumb."

Okay, so he didn’t actually say that, but he did walk me through the logical inconsistencies of wanting to do “real programming” that somehow didn’t involve the web in a meaningful way. He made it clear that I couldn’t do the larger things I wanted to do without some foundational knowledge best acquired by building a website.

I’d had a really dumb idea for a website I was actually interested in building. The idea was to present a user with an interface for putting in their birthday, then calculating the day they were conceived and looking up what the #1 song on the Billboard Hot 100 was that week, the implication being that if any song was most likely to be on the radio when your parents did the deed to bear your existence, it would likely be the most popular one. I also thought to include an interface for noting if you were a late or early delivery, as that obviously impacts the results.

I explained it to the man (who really just wanted to pick up his new headphones or whatever) and worried aloud that I didn’t think I could put such a silly thing on a résumé, and asked if he had any better ideas. He said something to the tune of “in this field, and in this city, you can put whatever the fuck you want on a résumé and they’ll probably bring you in.”

Actually building Porktrack⌗

I knew I had to start by collecting the relevant data first. I chose (and learned) Python in order to fetch the data because I’d read in Steven Levy’s In The Plex that Google had chosen Python for their web crawling tasks, and I didn’t know what cargo culting was. My first stab was to take the data from the Wikipedia pages for the Hot 100 chart by year (1959 as an example). Initially, this meant reading the HTML of the page as a string and using Python’s string find() and replace() methods on various HTML properties to extract the actual data. I say HTML properties and not, like, XPath because I definitely did not know what XPath was (and performed an actual facepalm when I finally discovered them).

This obviously didn’t scale well, as some of these pages are formatted wildly differently from each other. I briefly contemplated “standardizing” the formatting by being a particularly pedantic member of the Wikipedia community, but it didn’t feel appropriate to let this project have any lasting impacts on Wikipedia. In the oldest version of the source code that I can find, I’d already realized how poorly this scaled and ended up switching to a modified HTMLParser object. I probably went that way because a Stack Overflow post suggested that was how you scraped the web with Python.

The parser would traverse the elements on the page, and incremented state based on the current state. So, the data would come in the form of three table cells in a row, the first with the date, the second with the artist, and the third with the song title. Once the script got to where it could semi-reliably ascertain who had what hits when, it spat them out as SQL queries to stdout and saved the output as what I would learn is called a migration script. I would then execute the file’s query in PHPMyAdmin, which meant I had a database. Eventually, I modified the script so that it would also fetch the top YouTube video ID from a search for “{artist} {song_name}”.

My understanding of the LAMP stack was that it was literally[^1] the only way to make a website where the response was dynamic. I just dove straight into the Codecademy course for PHP. If you had told me you could write web servers in Python, I would have rejoiced, because building the scraper made me really fall in love with the language.

Development environment⌗

I didn’t know how to set up a local development environment and, indeed, was using Windows mostly, where these things tend to be harder than they should. My workflow ended up being that I would write PHP files on my local machine, transfer them to the appropriate place on the machine via FileZilla, and then hit the web page in order to see my changes. It is still, to this day, one of the best development environments I’ve ever had. I’m not even being kinda sarcastic. I love instant feedback, and had I gone through the process of setting up WAMP or whatever, I likely would have doubted that whatever was working on my machine would actually work on production. When your dev environment is production, though, no such doubt can exist. (Note: I am not recommending this workflow for anything meaningful.)

One of the main (only?) benefits to being a security guard is the downtime. Most of the time, your job is just to be present, but only physically. Most security guards don’t have access to a computer, and many times if they do, they are subject to rigorous IT net nanny policies because their computers are just a workstation in a warehouse full of workstations, and they aren’t going to provision them differently because the security guard is bored. We’re all bored. I was lucky, though, because I worked for a condo complex, so there were no IT firms, and the computer was a Dell shitbox I bought from the Office Depot myself on the HOA credit card, if I recall correctly. I was able to install Python on it and able to use IDLE during lulls in the workday in order to write the scripts that fetched data for the database. I was also able to install FileZilla and change the actual production website.

Infrastructure⌗

The only infrastructure provider I felt comfortable using was DigitalOcean, who I still think really deserve a lot of credit for building an interface that someone who knows nothing about programming can still use and feel like they haven’t screwed themselves out of a paycheck. I used the one-click-setup LAMP stack droplet. I don’t remember if this configuration came with PHPMyAdmin, but I didn’t know it existed before this experience, so it wouldn’t surprise me at all. I probably could have swung the $10/month droplet, but I stuck with $5 because of how little I made. I used DigitalOcean’s DNS tool and nameservers as well.

I eventually cooked up enough crappy PHP that the site did what I thought it should do. I was also learning HTML/CSS/JavaScript/SQL in order to accomplish this task, and I really enjoyed myself. I put the files onto the droplet via FTP, and the site seemed to work as I expected. I did some basic testing around awful input, but I didn’t understand what unit tests were or how to write them, so I didn’t do any of that.

15 minutes of fame⌗

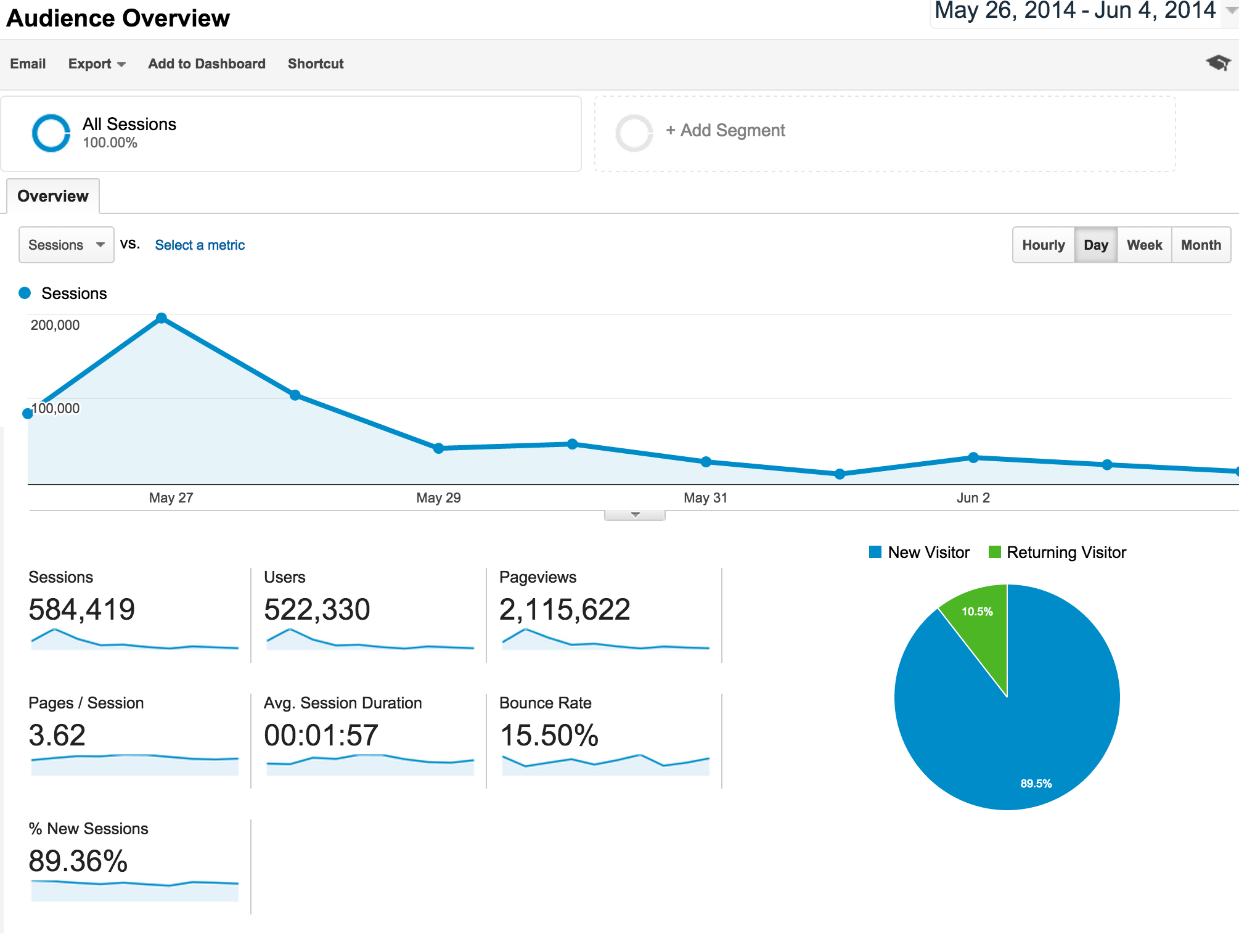

What happened next is still one of the wildest things to happen to me in my entire life. Once I felt like the site was in decent shape, I posted it onto /r/music, and it took off like a rocket. My post received thousands of upvotes and made it to the front page, which led Porktrack to receive just over 2.1M hits in the first 10 days it was live. I know this because I had the foresight to include Google Analytics on the page. The site didn’t have ads on it for almost all of it, if I recall correctly (eventually did place ads on the site via AdSense).

Most of the traffic fizzled out and died by mid June, but I kept checking the AdSense results because I had vowed to shut down Porktrack the month it stopped making enough to pay for its own droplet. Almost half a year later, I was running an errand and mindlessly checked AdSense to find that I had made $2,500 that day. It was the day before Thanksgiving, and someone had posted it to a different subreddit (that I can’t manage to find at the moment), where it was gaining a similar influx of traffic from bored Americans waiting for planes. I ended up making $3,300 after all was said and done, which was cool.

One of my favorite parts about this experience was other folks' reactions. People genuinely seemed to think the idea was amusing, and nobody seemed to be particularly offended. One of the other folks who lived at those condos was a guy who was part of a morning radio trio. He came up to the guardhouse the day after it went viral telling us about this crazy website his broadcasting company had approved as a topic of morning conversation. He explained to me that radio stations all over the country get the exact same list, and it’s up to the individual hosts to decide what they’ll talk about. He said they hadn’t opted to talk about it that morning, but he said it had been a close contender. The look on his face when he found out it was my website is something I don’t think I’ll ever forget, if I’m lucky.

Indeed, I was reached out to by a few different radio stations who let me know they spoke about my website on air. Some larger websites also wrote about the project, which I interpret not as a sign of incoming fame or fortune, but more as a sign that content folks are desperate to talk about anything at all.

edited audio clip of FM96 in London, ON, CA talking about Porktrack

edited audio clip of FM94.5 The Buzz in Houston, TX, US talking about Porktrack

Encouragement and detraction⌗

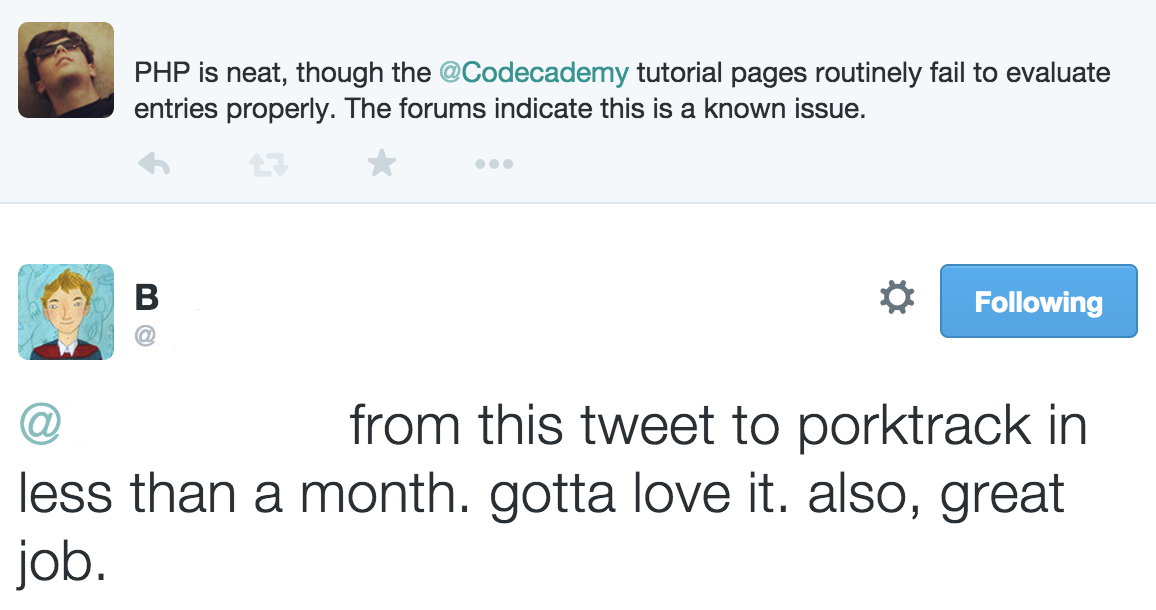

I mentioned in the comments on the Reddit post that it was my first website and I’d spent almost a month writing Python “scraping” code to get the database, and then built a website around it, yadda yadda. I thought I’d include this screenshot, as it was really motivating, and I think I even made it my desktop wallpaper for a hot second.

Some folks thought the idea was good and tried their own hands at building the app. I got contacted by somebody via Reddit message who said that someone had “copied” my website and made a Dutch (I think?) version of it. This is the only evidence I have that the website existed:

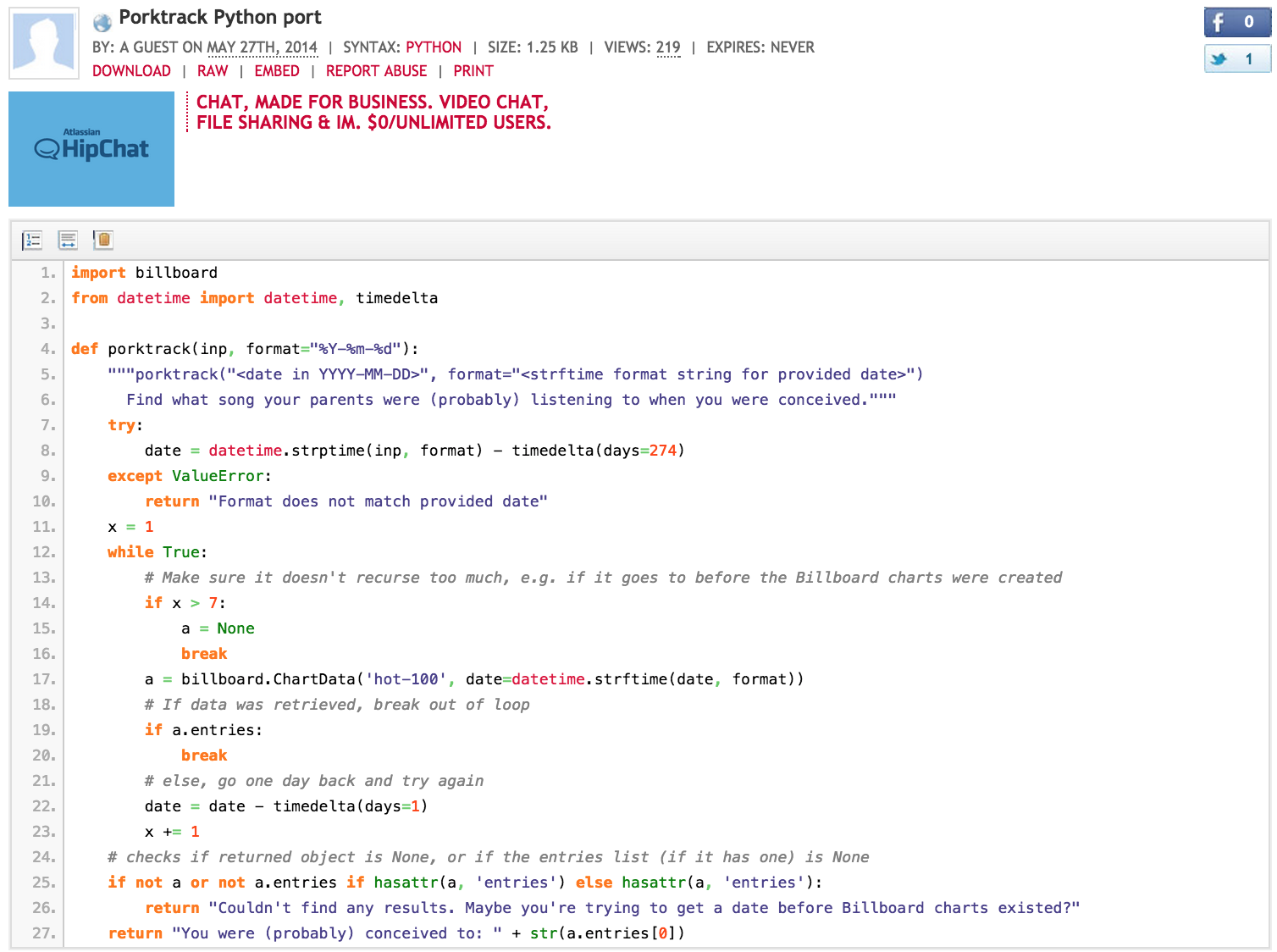

Another person had seen from the comments/tweets/looking at my code on GitHub that I was a beginner and took it upon themselves to implement it their own way and send it to me. It certainly looked nicer than any of the Python I’d written up to that point, and, for some reason, I kept this screenshot, likely smitten that anybody else would write code after something I’d written:

It is still the Internet, though, so there was, of course, the usual pettifoggery.

Database debacles⌗

Crucial to remember in all this is that for me, the request-response lifecycle, the notion of a CRUD app, was becoming obviously clear to me, and its power was palpable. “This is how the Internet works!” I rejoiced, with the realization that if I wanted to build a website for keeping track of cats I saw on the street, I was just a little schema and SQL away from having exactly that!

I was on top of the world and wanted to put my new knowledge to great use, so I did what any hapless fool in that circumstance would do: I reinvented analytics. I created a table in PHPMyAdmin that had columns for some basic stuff around timestamp, source IP, referring URL, etc. I queried this new database table the way you might expect of someone who doesn’t know what they’re doing: by opening a connection to it. Every time someone hit the website, the page would make two MySQL connections to the exact same database, one for the tracks, one for the analytics data.

Shortly after launching the site, folks objected to the process by which their Porktracks were determined, noting that their parents were immigrants/die-hard country fans/otherwise would never have listened to the Hot 100. So, I very quickly adapted my scripts to account for the country and Latin charts, created new tables for them, and queried them the way I had done thus far. Yup, another two connections.

This very quickly unraveled and resulted in my $5 DigitalOcean droplet soliciting union membership interest from the other droplets. I think it might actually be impossible to be stupid enough to look at a degraded web page initiating four connections to the same database and not figure out the solution, because I’m certain I would have just speechlessly accepted my plight if it were. After switching to just the one connection per request and eliminating data gathering in its entirety, I never had issues with the site going down ever again.

Even though I knew nothing, I knew that “real” websites did load tests and other validation work before shipping software. I allowed myself to be convinced that I shouldn’t put in similar efforts for this website because of how goofy it was. I didn’t want to be the person who spent a great deal of time making a gimmick website reliable, but as a consequence of that attitude, I suffered the failing defeat of having my site go down. I learned the very valuable lesson that if something is worth doing, it’s probably worth treating it like it’s going to be the sort of runaway success that would give you uptime problems. If you treat everything like it’s going to go gangbusters, then you’ll make very different decisions around how your application is designed/hosted/maintained.

The real benefit⌗

Ultimately, the consequence of building the site that I’m most grateful about was that it gave me something to do. I’d heard that single-page applications were a thing, and I didn’t know how they worked, but I had a working site receiving steady traffic. I would wait until late at night and cobble together some awkward vanilla JS, a results-specific route that spat out HTML, and accomplished a “single-page app” by replacing the .innerHTML field. Then, I heard that nobody writes JavaScript, everybody writes jQuery, so I rewrote my crappy vanilla JS into crappy jQuery JS. Then, I wanted to create a mobile app for it, so I started down that process too (but never actually finished it, probably to everybody’s benefit).

I got to where I was so comfortable talking shop with other software developers at meetups and such that they started to inquire where I was working and would react with disbelief upon learning that I was a security guard. I got a lot of encouragement from the Austin tech community in general, before or after feeling acclimated to the task. I eventually mustered up the courage to put together a résumé and started applying to junior developer jobs. I was told twice after being rejected that the novelty of Porktrack and the implied chutzpah required to put something like that on my résumé were too alluring for some folks to pass on at least an interview.

It took me a solid eight months of applying every day, going to interviews where the expectations were completely out of line with what I’d advertised on my résumé, and failing to get those jobs but getting better at and more comfortable with the process with each step. Eventually, I was hired at a startup as a junior web developer, and the rest of my career is what I’m in the middle of now.

Luck⌗

The thing I always try to emphasize when I recount this whole thing is that much of my “success” came in the form of good fortune. I was/am fortunate in so many ways:

-

I was fortunate that I didn’t have any children or sick relatives to tend to, and a supportive spouse, so I had all the time and space I needed to try and accomplish my goal. I routinely had 4+ hours of free time on weekdays and virtually the entire weekend to read tutorials and run little experiments. From what I gather, that would never fly in a house with a greater than zero amount of children.

-

I was also lucky to work at a place that was more than fine with me doing extracurricular activities while “on the job.” My bosses at the time both knew that I was working on Porktrack and that I wanted to find a way to be a software developer. They always allowed me to spend time at work reading about code or writing dumb programs, provided I took care of my actual work obligations (which I always did). They helped test Porktrack for me a few times, and when the time came to interview, they were very generous and understanding about the necessary away time I needed to attend them. If I had worked somewhere where resources were more scarce or had otherwise made myself intractably necessary somewhere, I don’t think I could have done it.

-

I mentioned this earlier, but it’s worth repeating that I am lucky that the friendly folks who lived at the condos indulged my endless pestering for suggestions on what to learn or work on next. I had actually managed to finagle an internship from one of them as a QA intern but got hired at the startup shortly after starting, so I left for that.

-

I was lucky that I lived in a city with an active tech economy/community. Most cities in the United States cannot facilitate the sort of access I took advantage of to learn from professionals. Many cities with good tech economies have pretty pitiful meetup scenes, too.

I worked really hard, to be certain, but all the hard work in the world would have been for naught if my situation had been like that of the average. I had a blast, got to bring folks a very small amount of joy, and it never once felt onerous. I feel sometimes as though I found a cheat code by accident. It’s not supposed to be that you can have a lot of fun and end up making good money. It’s supposed to be that you spend at least three decades doing menial tasks for people who don’t care about you and remark upon the expense of your wage with disgust.

Porktrack redux⌗

Recently, I saw this neat video where a man recreated his very first flipbook from 30 years ago:

I felt inspired, and obviously thought about my very first website and realized that I’ve learned so much in the last five years. Almost nothing about how I build personal projects is the same as it was. In fact, quite a few options for hosting such a website have come about in the intervening years. I resolved to rebuild the application and take the time to address some of the complaints I had as a maintainer back in the day. The main things I want to tackle:

- Scaling: Porktrack didn’t scale well at all, either up or down. I want to rebuild it in a way where it can be hosted basically forever, without costing me a tremendous amount of money to do so. Simply put, it’s not important enough to me to warrant $60/year to host. To give you an idea, if I can’t pay for this site’s hosting costs with a dime per month and have change in return, I will consider myself unsuccessful.

- Language: Shortly after starting my first job, I discovered Go and have not really written much Python outside of work since then. I want to rewrite the core components of Porktrack in Go.

- Data completeness: When I last ran Porktrack, I had a reminder every month to run the script again and add things to the database so that I wouldn’t lose track of that. I’d like the new version of the site to update itself as much as possible, without human intervention. Also, the YouTube video IDs I’d save would very frequently get axed for having copyrighted content, so I want to minimize that consequence to whatever extent I can.

Sketch out a plan⌗

The first order of business was to build the thing that fetched the database. In the old application, I had Python scripts that spat out SQL migrations for all the Porktracks. This was handy because it took a week or more before I finally felt like the script did the thing it was supposed to do every time. This way, in the event that the script got 95% of the entries correct but maybe futzed up a single quote here or there, I could just manually fix it in a text editor without having to add a conditional to my code or otherwise write a bunch of safeguards.

This time around, I’m doing something similar, only I’m writing to a local SQLite database that doesn’t get added to version control. This accomplishes a few things:

- It gives me a similar sort of in-between inspection scheme where I can validate that the data looks the way it’s supposed to.

- It makes it so that I don’t have to constantly fetch from Billboard and risk detection/IP blocking.

- Lots of tools exist for querying a local SQLite database.

Architectural choices⌗

I decided to host the application on Cloud Run. Cloud Run is a managed serverless application platform, announced this year at Google Next, where you publish a container to a private registry and then tell GCP to associate that container with an HTTPS-enabled URL, which will execute your server when it receives a request. Like most serverless schemes, you are only charged for the time your application is alive. Thankfully, you just write a server. Standard routing frameworks work just fine.

There is one main consideration for serverless applications, however, which is the database. Cloud SQL is completely viable for Cloud Run use, (and as a matter of fact, the Cloud Run interface provides a convenient mechanism for pre-defining Cloud SQL connections) but a Cloud SQL instance costs ~$8/month minimum, which, as we all know, is greater than a dime. Cloud Firestore, however, supports tons of simultaneous connections for queries and gives you (as of the time of this writing) 50,000 free queries per day.

I ended up using the Spotify API to provide sound samples of the songs instead of YouTube. In the years since I last built Porktrack, YouTube has started requiring JavaScript to load search results, and their API limitations are, in my humble opinion, disrespectful. There basically wasn’t a way I felt comfortable retrieving that data and validating that it was still relevant, whereas from what I can tell, the Spotify IDs are more permanent.

So, I’ve rewritten Porktrack as an entirely serverless application and made a serverless data store its primary source of truth. I have code that initializes the database locally, and after the local SQLite database is loaded and I feel confident that data is collected well, I run a simple function that will iterate over every entry in this database and save it to a Cloud Firestore collection.

I also have a Cloud Function being activated by a Cloud Scheduler job once a week on Sundays to check the Billboard site and run the same function that gets run when we build the SQLite database, and then save that data into Cloud Firestore.

I got to handle the scaling problems by waiting for infrastructure providers to get WAY better at what they did. I got to port it from a good language to a better one, and I don’t have to set a reminder on my phone to run a script and execute some SQL, because managed infrastructure will handle that for me. You can check out the current version of the site by going to https://www.porktrack.com.

Update 2/1/20⌗

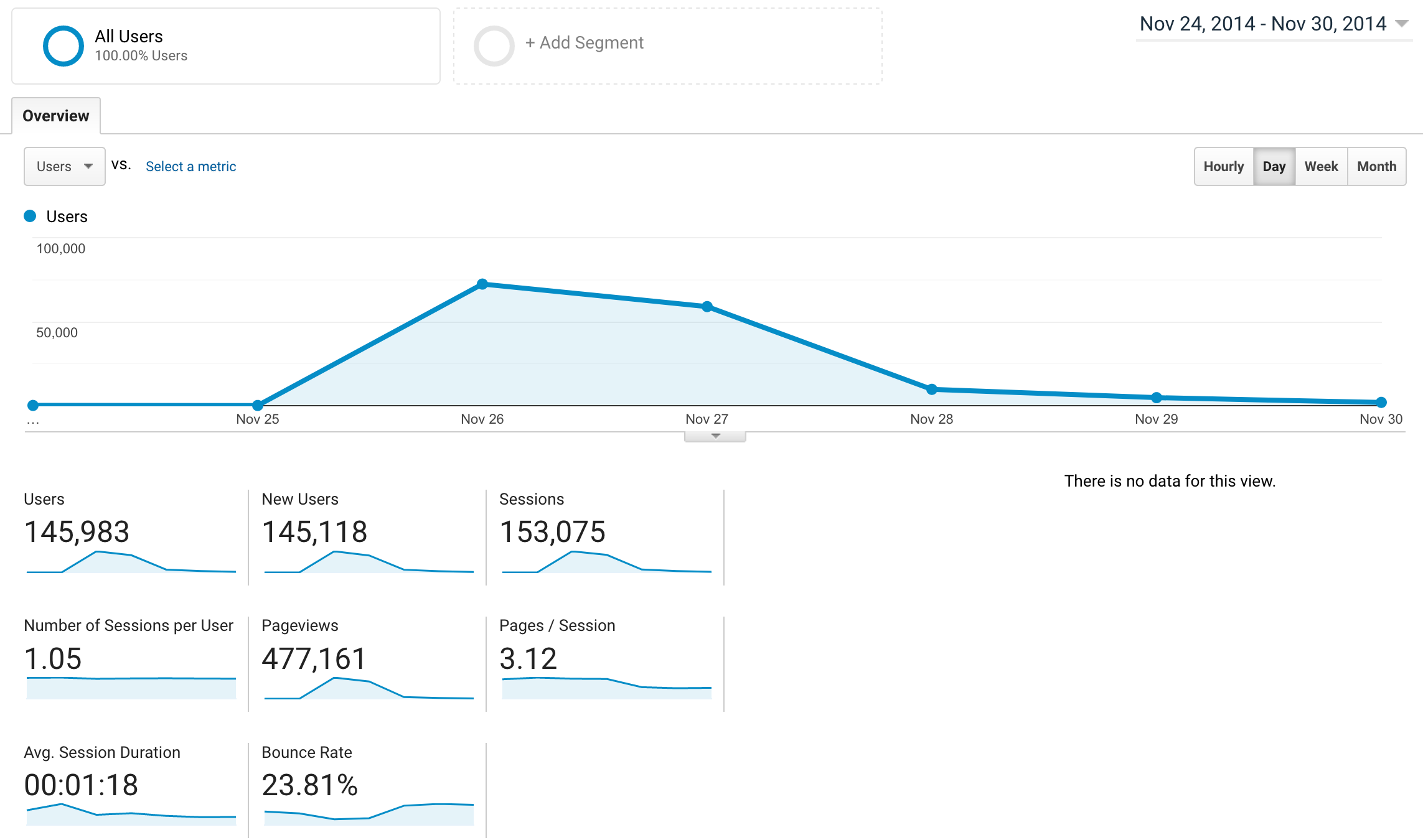

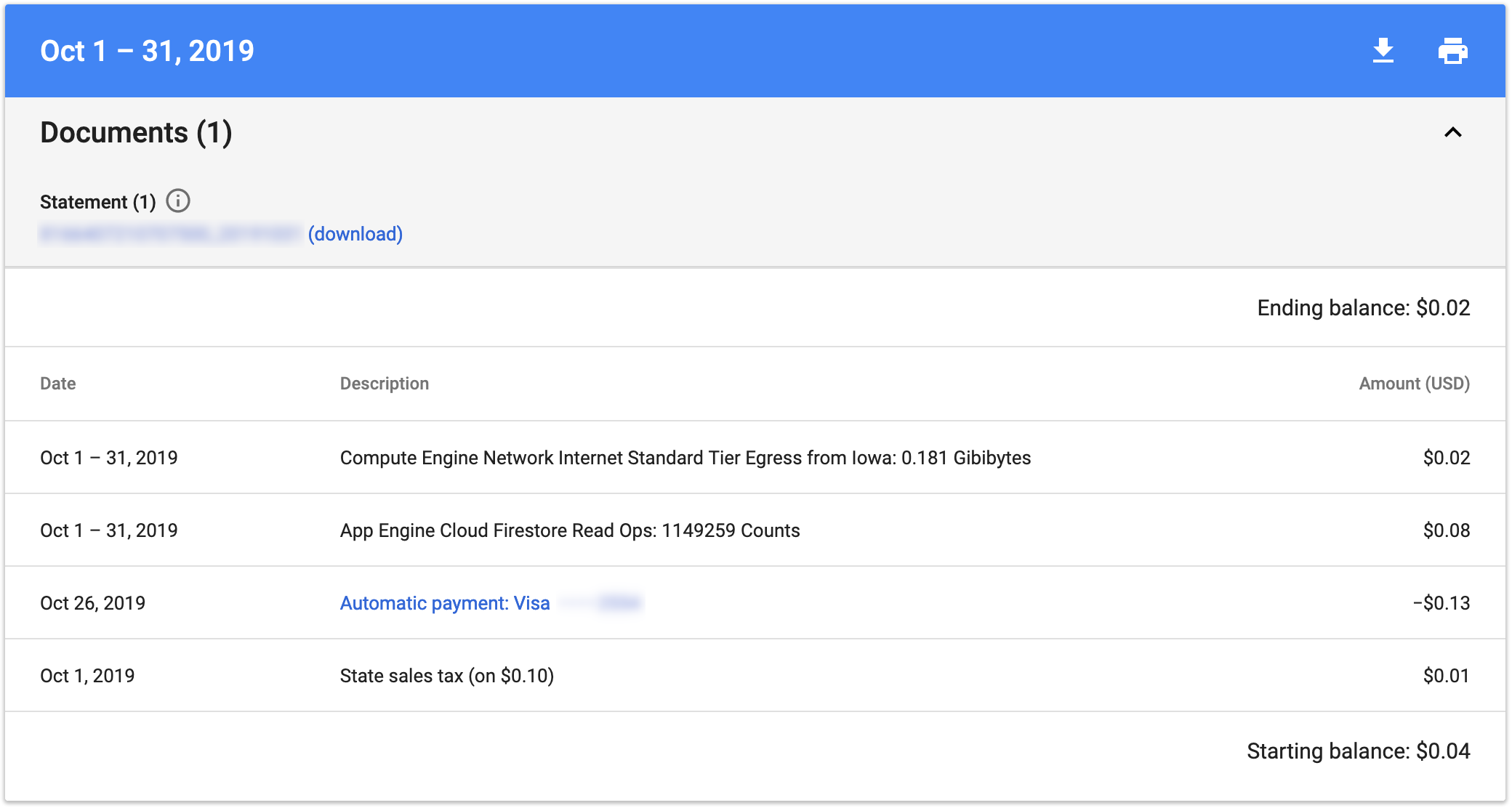

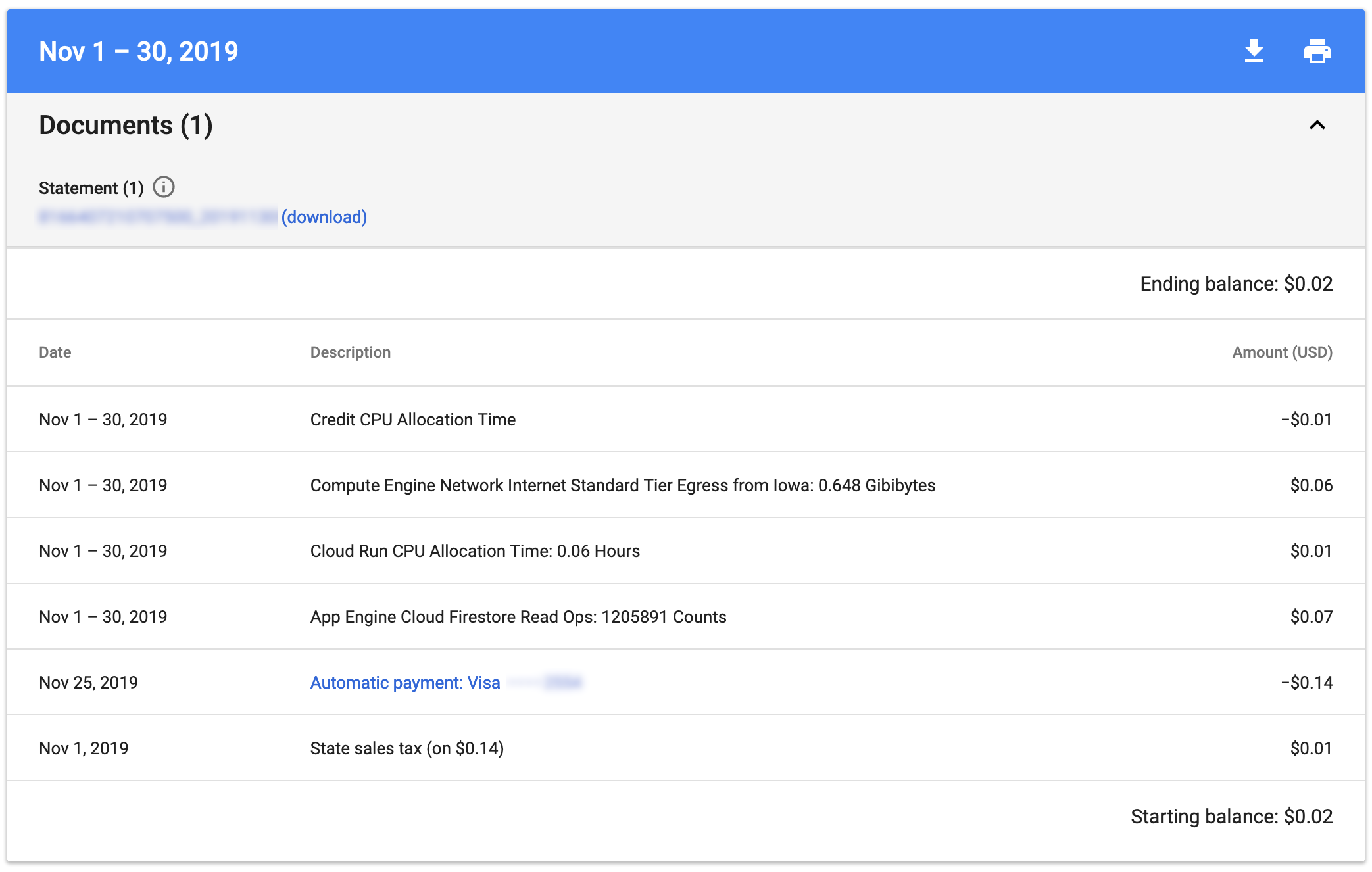

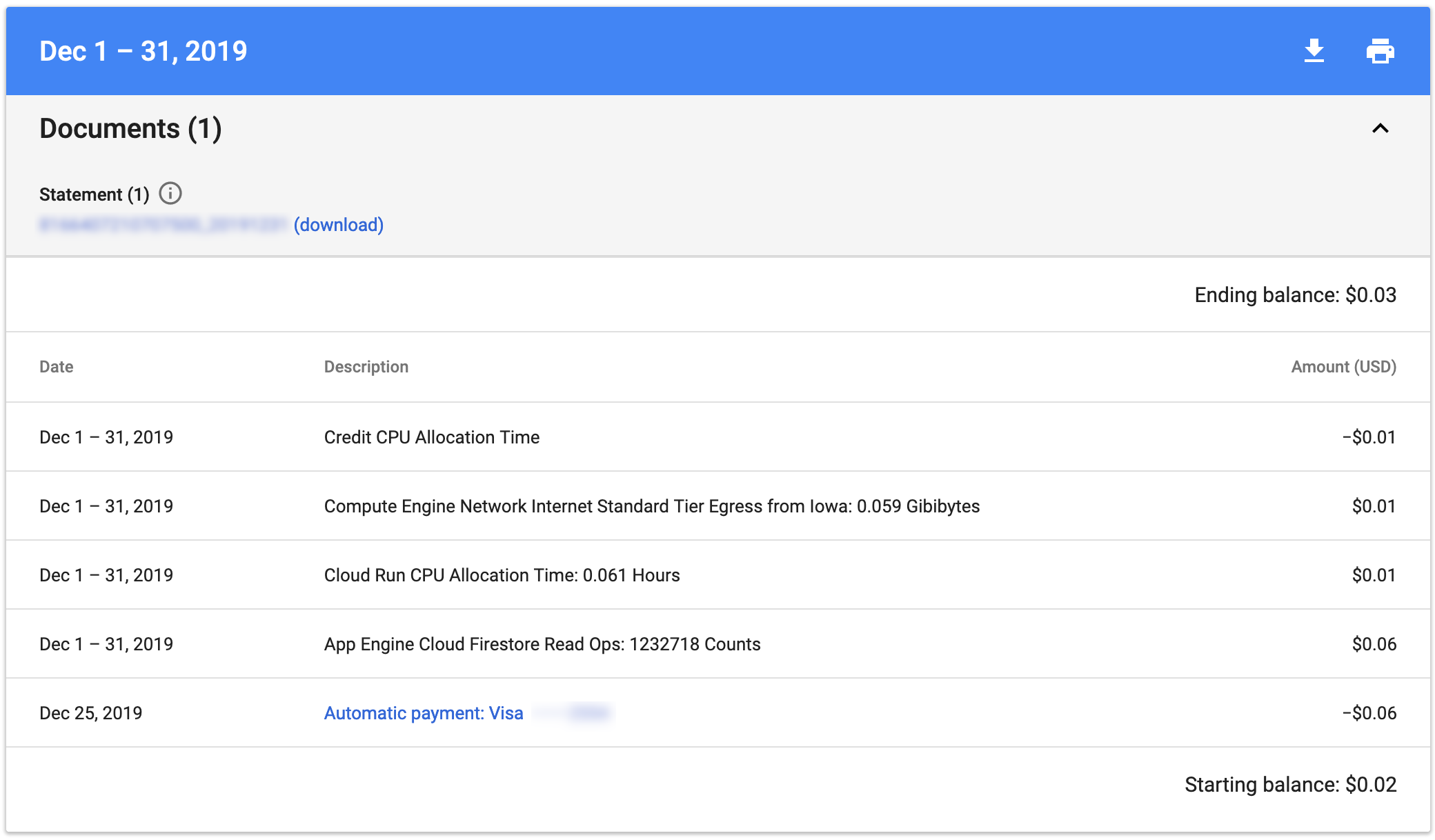

The new app has been running for a few months now, I wanted to demonstrate the actual monthly costs of the app.

Here’s October 2019’s bill:

Here’s November 2019’s bill:

Here’s December 2019’s bill:

I’ve shut down the site now, since I’ve proven my point, and really, this site shouldn’t exist. :)

[^1] I mean literally literally, not figuratively literally.