Greener Cloud Pastures

Preface⌗

I want to take the time before writing to note that I have great respect and appreciation for the folks who work at any of the companies mentioned and/or on any of the products mentioned. Computers are hard; making stuff that is primarily meant to be consumed by them is even harder. My goals here are similar to those of that post. I hope that there can be something constructive that comes out of this post, but at the very worst, I hope it simply doesn’t offend or disparage anybody.

Background⌗

In my last article, I wrote about my endeavor to get a side project deployed to a professional cloud, specifically AWS. To briefly summarize, it didn’t end up going to plan, and it proved to be quite expensive to host a very simple application there. I still want to host this application somewhere, so I started to look at alternatives to AWS for deployment.

After all was said and done, I was left with a lot of indecision and fatigue. I liked the level of service quality I got from AWS; I just really didn’t like paying for it. When I thought about all the moving bits and pieces of the application, it just didn’t feel like this thing should cost more than, say, $40 at most to host per month. I was hoping I could land somewhere that would serve my app basically just as well for about 1/3 of the price if at all possible.

What I wanted from a provider on the technical side was simply a way to ship an app container and have the provider put it on the public internet. Let me connect that container to a database, maybe some object storage, and a queue, and I’ll be good to go.

First Candidate: DOAP⌗

I started to look at DigitalOcean’s App Platform, which seemed to touch a lot of these bases. I could define a containerized app, explicitly associate a database with it, and leave the rest to them.

After playing with this for about two days, I ended up deciding against it. It seemed to work well enough, but I also felt like I was gracing the outer limits of when it was appropriate to use the platform. It felt as though if my app decided to do even one more thing, I wouldn’t be able to host it that way anymore. That I’d be back to the same drawing board I was sitting at in no time.

I was left with the impression that the target audience for App Platform is agencies ñ folks approached by non-technical parties who need a specific kind of application to be made and hosted. I could see a workflow where you basically just have one App Platform definition you use to deploy any number of hyper-similar WordPress sites or whatever. If the client came back and asked for something that exceeded the capabilities of DOAP, the agency could just quote a wild price, but I’m trying to avoid wild prices.

DigitalOcean Shortcomings⌗

One thing I made very heavy use of on AWS was managed services, specifically RDS and SQS. Being able to have a queue without having to worry about that queue’s infrastructure was very nice, but DigitalOcean has no analog for these. You could probably write up an App Platform template for deploying a containerized version of NATS or whatever, and they do have a managed Redis offering, but it’s much more expensive ($15/month at the time of writing) than SQS (consumption-based, with a generous free tier ñ one of the few things that didn’t cost me money on AWS). I also just sort of liked not having to think about it as anything other than a generic queue.

Kubernetes⌗

One thing DigitalOcean does have that is actually priced fairly decently is their managed Kubernetes offering. Previously, I have stated that using Kubernetes is a mistake until proven otherwise. I violated these tenets and explored using Kubernetes for this app in DigitalOcean for about three days before I gave up. I should have trusted my gut.

I could probably write an article just on why Kubernetes didn’t work out, but I’ll spare us all the misery. I got as far as having a local Kubernetes setup for the app that worked, but I could never manage to get the one in DigitalOcean connected to the public internet.

Where to Now?⌗

So, I’ve fully ruled out DigitalOcean, App Platform, and the Kubernetes offering, which leaves only Azure and Google Cloud Platform (GCP).

Azure has a number of container hosting solutions, but the one that seems most akin to ECS is called Azure Container Apps. It’s in preview and was launched very recently, so while I’m sure it’s probably fine, I don’t really have a lot of confidence using it just yet. They also have AKS ñ a managed Kubernetes offering ñ but I’m not doing that either, for the aforementioned reasons.

I’ve used GCP before in my career and for side projects. This very blog is hosted there, as a static site, and I pay something like $20/year all said and done. When I worked at WP Engine, we made very heavy use of GCP for all of our internal software and a not insignificant chunk of our actual business offering as well, so I had a vague impression of its production reliability. Somewhat like my AWS experience, I’d only really bothered writing code that deployed there, not actually deploying it. (I did have a fairly successful endeavor a few years ago to rebuild and redeploy an old application to Cloud Run that went very well.)

I decided to give GCP a shot.

App Recap⌗

To briefly recall the app we’re talking about and its needs, it’s a meal management app. You put in recipes, create meal plans for the week from those recipes, and allow others in your household to participate. From a technical perspective, it needs:

- a database

- a server container

- an event queue

- something to trigger code execution when events arrive on the queue

I decided to use Cloud Run to host the server container, Cloud SQL for the database, Cloud Pub/Sub for the event queue, and Cloud Functions for the event responders. GCP supports assigning Cloud Functions as responders to Pub/Sub events, like how you can configure Lambda functions to respond to SQS events.

GCP Terraform Obstacles⌗

One goal I maintained from the prior effort was to have it so that the full environment could be spun up from nothing. That I could take a bare project with no resources and, after one CI task run, have the full app running and available. This was beneficial last time in reducing costs, since I could use Terraform to destroy everything in one run if I met this condition.

AWS allowed me to accomplish this particular goal. I could go from having nothing to having the full environment up in 30 minutes, with no preconfiguration in my AWS account other than the Terraform Cloud user stuff (which I’m not counting).

GCP, however, had a bunch of hurdles in the way for me. For one, every API needs explicit authorization.

- Want to create a Container Registry? You must first enable the Container Registry API.

- Want to administer Cloud SQL databases? You must first enable the Cloud SQL Admin API.

- Want to administer Cloud Run instances? You must first enable the Cloud Run Admin API.

After a while of playing API authorization whack-a-mole, I discovered what I thought would be a shortcut to this step:

- Enable the Cloud Resource Manager API

- Use Terraform to enable all the stuff I’d need with google_project_service resources.

This didn’t work. In fact, it did the opposite of working. Because I (foolishly) decided to add a bunch of the aforementioned resources that I had already enabled by hand, and hadn’t granted the lesser Terraform Cloud user rights to disable these things, it really messed with my Terraform state. Thankfully, cleaning that up is easy, but I learned so that you don’t have to, hopefully.

Additionally, for things like Domain verification (ugh), there didn’t immediately appear to be a good way of doing that automatically, which I’m not exactly against.

I will say, the GCP Terraform provider does a better job of catching errors in the “terraform validate” process. Many times with the AWS work, I would have something pass “validate” but fail to “apply” for something that could have totally been caught in “validate”. I very much appreciate whoever is responsible for this improvement.

IAM Woes⌗

IAM is also pretty confusing. In the console, users are called “Principals”, but in some old docs and guides, they seem to just be called “Users”? Users can have roles and service accounts, and those service accounts can have a subset of roles. I think I’ve recalled all this correctly, but I’m not confident I have!

Another thing that threw me for a loop was how to create a user for the Cloud Run API service. The Terraform definition has space for a Service Account ID, so I created a service account in Terraform and assigned it the “Secret Manager Secret Accessor” role. Only, Terraform gave me an error:

| Error: Error setting IAM policy for service account 'projects/xxxxxxxxxxx/serviceAccounts/[email protected]': googleapi: Error 400: Role roles/secretmanager.secretAccessor is not supported for this resource., badRequest

(Yes, the ., badRequest part is really in there.)

So, I needed a Principal, and it took me a while to figure out the right incantation of Terraform to produce it, because they are not named kindly:

resource "google_service_account" "api_server_account" {

account_id = "api-server"

display_name = "API Server"

}

resource "google_project_iam_member" "api_server_user" {

project = local.project_id

role = "roles/viewer"

member = format("serviceAccount:%s", google_service_account.api_server_account.email)

}

From there, you can grant that Principal specific roled permissions:

resource "google_project_iam_binding" "api_user_secret_accessor" {

project = local.project_id

role = "roles/secretmanager.secretAccessor"

members = [

google_project_iam_member.api_server_user.member,

]

}

and then assign it to your Cloud Run app:

resource "google_cloud_run_service" "api_server" {

name = "api-server"

location = "us-central1"

traffic {

percent = 100

latest_revision = true

}

autogenerate_revision_name = true

template {

spec {

service_account_name = google_service_account.api_server_account.email

}

}

# yadda yadda yadda

}

This, combined with some new code to handle environment-mounted secrets, led to my first “successful” deployment to Cloud Run. Only, I couldn’t access it because I hadn’t granted “allUsers” the permission to invoke this particular Cloud Run application. Nice default, I think, but requires more terraform IAM finagling:

data "google_iam_policy" "public_access" {

binding {

role = "roles/run.invoker"

members = [

"allUsers",

]

}

}

resource "google_cloud_run_service_iam_policy" "public_access" {

location = google_cloud_run_service.api_server.location

project = google_cloud_run_service.api_server.project

service = google_cloud_run_service.api_server.name

policy_data = data.google_iam_policy.public_access.policy_data

}

This is called out in the Terraform docs for GCP’s Cloud Run resource, but it’s called “noauth”, which I somehow failed to parse as “make public”.

Cloud Run DNS Woes⌗

Another thing I couldn’t manage to automate my way out of was the explicit domain name association that GCP requires for Cloud Run. When you create a Cloud Run service, you get a URL like “https://app-name-blah-blah-blah.run.app”, which you can’t just CNAME. So, you instead have to create a “Domain Mapping” that seems to tell Google’s routers, “It’s okay to respect this other domain.” The IAM around this is really funky, though. The Cloud Run IAM Roles documentation page explicitly calls out that:

Roles only apply to Cloud Run services, they do not apply to Cloud Run domain mappings. The Project > Editor role is needed to create or update domain mappings.

“So much for my preciously curated list of permissions; stupid Terraform has to be an editor!” I cursed. Only it turned out that even when I granted it that permission, Terraform still couldn’t manage the domain mapping. I kept getting the same error over and over again:

| Error: Error waiting to create DomainMapping: resource is in failed state "Ready:False", message: Caller is not authorized to administer the domain 'web.site'. If you own 'web.site', you can obtain authorization by verifying ownership of the domain, or any of its parent domains, via the Webmaster Central portal: https://www.google.com/webmasters/verification/verification?domain=web.site. We recommend verifying ownership of the largest scope you wish to use with subdomains (e.g. verify 'example.com' if you wish to map 'subdomain.example.com').

That link would take me to a page that gleefully told me I had already verified it. I think it was just the case that the Terraform user isn’t the explicit owner of the Domain like I am? Honestly not sure what happened here. I resolved to manage the damn mapping manually myself, which worked.

Cloud Functions vs. Lambda⌗

When I used Lambda, I quite liked that I could provide it a compiled binary in a zip folder. It felt a little old fashioned, but it definitely worked. Cloud Functions works with a little more magic ñ the bad kind. Rather than provide a binary, you upload code to a Google Cloud Storage bucket, and that sets up a Cloud Build trigger, which runs a preconfigured script against the code in question depending on your chosen runtime. Getting even a simple Cloud Function to upload via Terraform proved very difficult for me.

While nearly all the provided example Cloud Function code samples work, they do so because they don’t use anything but the standard library. If you want to use any of your own private code as libraries in your Cloud Function, you basically have to have a “go.mod” file per Cloud Function. This is pretty different from how I write Go code day to day, where I generally have exactly one go.mod file per repository. No big whoop.

Building Cloud Function artifacts can be done with the “pack” CLI for local testing, but you can’t ship those artifacts to Cloud Functions, you can only ship raw code to be built by Cloud Build. Maybe it’s documented somewhere, but this whole build process felt very opaque and yields confusing errors that didn’t aid me in diagnosis. Some examples:

Info 2022-02-08 19:48:39.274 CST Step #1 - "build": ERROR: No buildpack groups passed detection.

Info 2022-02-08 19:48:39.274 CST Step #1 - "build": ERROR: Please check that you are running against the correct path.

Info 2022-02-08 19:48:39.274 CST Step #1 - "build": ERROR: failed to detect: no buildpacks participating.

(I was uploading a .zip that had an empty folder in it.)

Info 2022-02-08 22:26:55.090 CST Step #1 - "build": Running "go run /cnb/buildpacks/google.go.functions-framework/0.9.4/converter/get_package/main.go -dir /workspace/serverless_function_source_code (GOCACHE=/layers/google.go.functions-framework/gcpbuildpack-tmp/app)"

Info 2022-02-08 22:26:55.270 CST Step #1 - "build": 2022/02/09 04:26:55 Unable to extract package name and imports: unable to find Go package in /workspace/serverless_function_source_code.

Info 2022-02-08 22:26:55.272 CST Step #1 - "build": exit status 1

Info 2022-02-08 22:26:55.278 CST Step #1 - "build": Done "go run /cnb/buildpacks/google.go.functions-framework/0.9.4/c..." (187.47553ms)

Info 2022-02-08 22:26:55.278 CST Step #1 - "build": Failure: (ID: 7a420ccf) 2022/02/09 04:26:55 Unable to extract package name and imports: unable to find Go package in /workspace/serverless_function_source_code.

Info 2022-02-08 22:26:55.278 CST Step #1 - "build": exit status 1

(No root-level Go file.)

Info 2022-02-09 23:25:32.516 CST Step #1 - "build": Done "go list -m" (4.498213ms)

Info 2022-02-09 23:25:32.516 CST Step #1 - "build": Failure: (ID: 03a1e2f7) ...ry.io/otel/exporters/otlp/internal/[email protected]: is explicitly required in go.mod, but not marked as explicit in vendor/modules.txt

Info 2022-02-09 23:25:32.516 CST Step #1 - "build": go.opentelemetry.io/otel/exporters/otlp/[email protected]: is explicitly required in go.mod, but not marked as explicit in vendor/modules.txt

Info 2022-02-09 23:25:32.516 CST Step #1 - "build": go.opentelemetry.io/otel/exporters/otlp/otlpmetric/[email protected]: is explicitly required in go.mod, but not marked as explicit in vendor/modules.txt

Info 2022-02-09 23:25:32.516 CST Step #1 - "build": go.opentelemetry.io/otel/exporters/otlp/[email protected]: is explicitly required in go.mod, but not marked as explicit in vendor/modules.txt

Info 2022-02-09 23:25:32.516 CST Step #1 - "build": go.opentelemetry.io/otel/internal/[email protected]: is explicitly required in go.mod, but not marked as explicit in vendor/modules.txt

...A few dozen more of those.

Info 2022-02-09 23:25:32.516 CST Step #1 - "build": To ignore the vendor directory, use -mod=readonly or -mod=mod.

Info 2022-02-09 23:25:32.516 CST Step #1 - "build": To sync the vendor directory, run:

Info 2022-02-09 23:25:32.516 CST Step #1 - "build": go mod vendor

(This was from trying to not have more than one go.mod file. I’d never seen this error in any Go I’ve ever written before.)

- "build": Failure: (ID: 7a966edd) vendored dependencies must include "github.com/GoogleCloudPlatform/functions-framework-go"; if your function does not depend on the module, please add a blank import: `_ "github.com/GoogleCloudPlatform/functions-framework-go/funcframework"`

(The why behind this is never really explained, but I’m not worried about a random empty import.)

All said and done, it took me two evenings staying up to 1:30AM or so to get all the lights to turn green.

Cloud Function Woes⌗

I kept trying to diagnose why the function that finalizes meal plans was failing, and it didn’t seem to matter what I changed in code, the subsequent logs would never show up. I was eventually able to suss out that Terraform wasn’t updating my Cloud Function at all. It was still on version one, despite a dozen or so “successful” deploys. It turned out I wasn’t the only person who had experienced this, and after applying that solution, was finally able to start debugging in proper form.

After some normal user errors, I encountered an issue getting my now-running Cloud Function to connect to the database.

Cloud SQL connection failed. Please see https://cloud.google.com/sql/docs/mysql/connect-overview for additional details: ensure that the account has access to "xxxxxxxx-dev:us-central1:dev" (and make sure there's no typo in that name). Error during generateEphemeral for xxxxxxxx-dev:us-central1:dev: googleapi: Error 403: The client is not authorized to make this request., notAuthorized

(Again, the “., notAuthorized” part was actually present in the output. Funnily enough, every time I get errors related to this, they link to the MySQL docs even though I’m using the Postgres version of CloudSQL. I let it pass because you can easily navigate to the Postgres version from those docs.)

Cloud Run Woes⌗

Cloud Run was not without its own, similar, issues. I’d be updating code and a new revision wouldn’t get deployed. I realized I was probably asking too much of Terraform here, so I tried to go about it via the official Github Action for deploying Cloud Run services. Immediately, I encountered an error:

ERROR: (gcloud.run.deploy) PERMISSION_DENIED: Permission `iam.serviceaccounts.actAs` denied on service account [email protected] (or it may not exist).

After some searching, I happened upon this StackOverflow answer for precisely this problem and realized I needed to add the “Service Account User” permission to my GitHub Deployer IAM Principal. This caused my next deploy to work, but the one after that failed with the familiar error message. I discovered that somehow the Service Account User role was being removed from the Google Actions user after each deploy. So I put the relevant permission (“iam.serviceaccounts.actAs”) in a custom role and gave that role to the Actions user. That worked, and I could continue deploying without interruption.

Database Connectivity⌗

On AWS, whenever I needed to talk to the database, I employed this awful trick where I would spin up a Cloud 9 instance and use the terminal for that instance to connect to the RDS instance. Since the RDS instance wasn’t configured for public connectivity, this was the only way I could manage to run raw queries against it.

For GCP, this is even harder because, by default, the Postgres instances are configured to reject connections that don’t have TLS enabled, and the certs you can download from the GCP interface don’t seem to work on localhost or with an app like Beekeeper. You can connect via Cloud Shell, but you can’t use the certs there either.

The only way I’ve found to consistently run raw queries against the database is to temporarily disable the TLS requirement and then connect from the Cloud Shell while remembering to reactivate it. Kind of painful, but not the world’s biggest inconvenience.

Google Cloud Console⌗

Just a quick note, but I quite like it, actually. It’s just as easy to find things on GCP as it is on AWS. One complaint is that the interface, at times, completely fails to work if you disable common NoScript domains like “googletagmanager.com”.

Static Site Woes⌗

This project also makes use of Google Cloud Storage for the static page that interacts with the API. When I tried to create a bucket with the appropriate name for my domain in GCP, I encountered this error:

The bucket you tried to create is a domain name owned by another user.

This ended up being that my Terraform service account user wasn’t listed as an owner of the domain in the Webmaster controls. Adding it was easy enough, but the form didn’t trim whitespace so complained that the service account I provided it with (which has a “.iam.gserviceaccount.com” domain name) was not a valid Google account. Deleting the very hard to notice leading space was the ticket, though.

Monitoring Improvements⌗

One of the worst things about AWS was feeling like I basically could not have metrics or decent traces, feeling like I had to use X-Ray because of the state of the observability product market. Happy to report that Cloud Trace is leagues better than X-Ray, in my opinion, as is the log manager for GCP. This service collects 100% of traces the service produces.

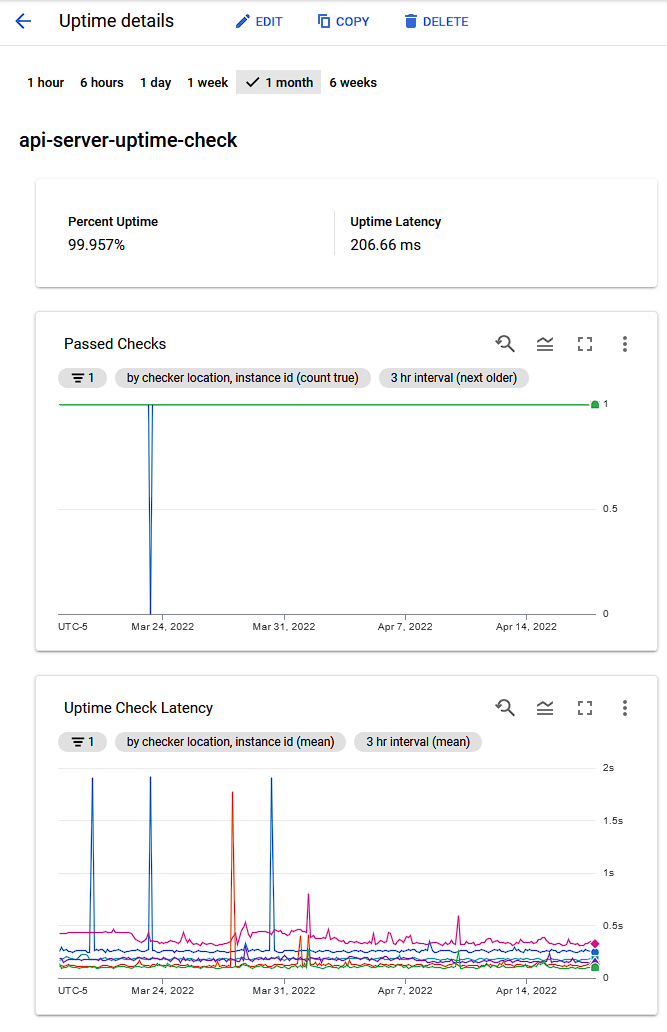

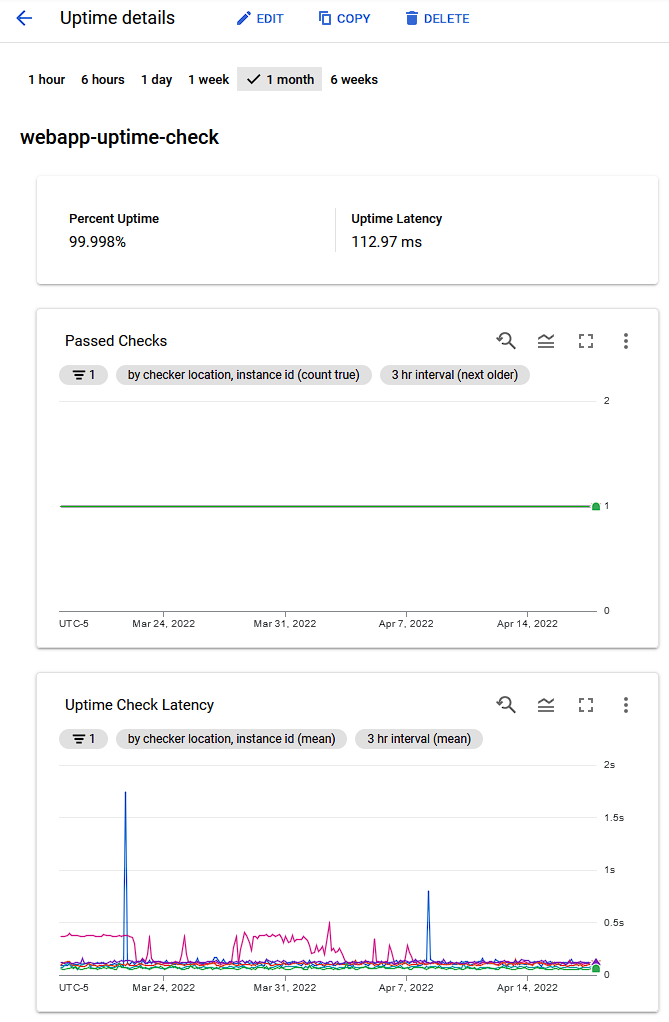

Additionally, GCP has these things called Uptime Checks, which, uh, make HTTP requests to your hosted services and report on the latency encountered. I was able to set one up for both the user-facing static webapp and the API server being hosted in Cloud Run.

As you can see, aside from the occasional outlier, it’s been pretty reliable. One thing I wasn’t able to accomplish in either AWS or GCP was app-level metrics, specifically Go runtime metrics. Locally, I can visualize how much time is spent, for instance, collecting garbage, but I cannot do this on GCP. Rather, I probably could, but my understanding of how Cloud Run operates is that the application itself is spun up and down depending on inbound traffic, so I’m not sure that collecting them would even be useful under that scheme.

Frontend Cookie Frustrations⌗

The webapp for this service is a static site, which talks to the API server over HTTP, authenticated by a cookie. The API server issues a cookie for the “www.” part of the app, but the browser will not include this cookie in requests to the API server because it has a different subdomain. Something needs to watch for requests to a given set of path prefixes on the webapp and forward it to the API service.

On AWS, I was able to use a CloudFront Distribution to do this:

ordered_cache_behavior {

path_pattern = "/api/v1/*"

allowed_methods = ["GET", "HEAD", "OPTIONS", "PUT", "POST", "PATCH", "DELETE"]

cached_methods = ["GET", "HEAD", "OPTIONS"]

target_origin_id = local.api_origin_id

forwarded_values {

query_string = true

headers = ["Origin"]

cookies {

forward = "whitelist"

whitelisted_names = ["servicecookie"]

}

}

min_ttl = 0

default_ttl = 0

max_ttl = 0

compress = true

viewer_protocol_policy = "redirect-to-https"

}

It’s been long enough that I can’t explain to you how that worked, but I can testify that it did work. GCP’s Cloud Storage doesn’t, as far as I can discern, have a comparable feature. Locally, I was solving this problem by having a Caddy instance that proxied requests, so I thought maybe deploying a Caddy instance would be the most effortless solution, but I’d just use Cloud Run to host it, which would mean I’m effectively paying twice for any request made to the API service.

Cloudflare Workers ended up being the solution that worked best for me. They have an example that I was able to very easily adapt to my usecase:

addEventListener('fetch', event => {

event.respondWith(handleRequest(event.request));

});

async function handleRequest(request) {

var url = new URL(request.url);

if (url.pathname.startsWith('/api/') || url.pathname.startsWith('/users/')) {

url.hostname = 'api.service.dev';

}

return await fetch(url, request);

}

And the corresponding Terraform:

resource "cloudflare_worker_script" "dev_reverse_proxy" {

name = "dev_reverse_proxy"

content = file("reverse_proxy.js")

}

resource "cloudflare_worker_route" "users_route" {

zone_id = var.CLOUDFLARE_ZONE_ID

pattern = "https://www.service.dev/users/*"

script_name = cloudflare_worker_script.dev_reverse_proxy.name

}

resource "cloudflare_worker_route" "api_route" {

zone_id = var.CLOUDFLARE_ZONE_ID

pattern = "https://www.service.dev/api/*"

script_name = cloudflare_worker_script.dev_reverse_proxy.name

}

Cloudflare Workers come with a quite generous free tier, which I’m not worried about really ever exhausting.

Pricing Outcomes⌗

Since the impetus to all this was the price for AWS, it seems fair to evaluate the price of running on GCP. Just so we’re all up to date, here’s what the bill is for:

- A Cloud SQL Postgres 13 instance running 24/7

- A Cloud Run API server running when traffic is received

- A Pub/Sub topic that triggers Cloud Functions

- Cloud Functions that run on a cron to manipulate data

- Prober Cloud Functions that run every five minutes and actually make use of the hosted service.

The prober function basically signs up a four-person household, creates some recipes, creates a meal plan, and votes on it for all members. It then verifies that the finalizer is running by waiting until the meal plan is finalized after all votes are in. So, I’m actually getting regular traffic to this service.

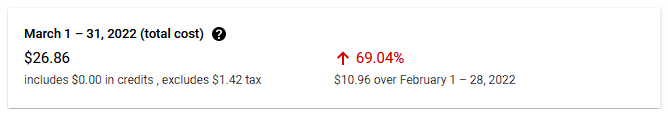

Here’s the bill I received for running the service in March. I’ve left out details specific to my account like the ID of the project, about $5 in credits towards my account, as well as things like SKU IDs which are probably not unique but are definitely not helpful in understanding the cost.

| Service description | SKU description | Cost type | Usage start date | Usage end date | Usage amount | Usage unit | Unrounded Cost ($) | Cost ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cloud SQL | Cloud SQL for PostgreSQL: Zonal - Micro instance in Americas | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 742.765 | hour | 7.799017 | 7.8 |

| Stackdriver Trace | Spans ingested | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | “36,903,907” | count | 6.877799 | 6.88 |

| Cloud SQL | Cloud SQL for PostgreSQL: Zonal - Standard storage in Americas | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 19.994 | gibibyte month | 3.398864 | 3.4 |

| Secret Manager | Secret access operations | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | “1,004,162” | count | 2.982484 | 2.98 |

| Cloud Run | CPU Allocation Time | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | “124,279.60” | vCPU-second | 2.981886 | 2.98 |

| Cloud Functions | CPU Time | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | “197,184.96” | GHz-second | 1.968551 | 1.97 |

| Cloud Functions | Memory Time | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | “123,073.24” | gibibyte second | 0.304218 | 0.3 |

| Secret Manager | Secret version replica storage | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 8.997 | month | 0.179528 | 0.18 |

| Cloud Run | Memory Allocation Time | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | “62,138.05” | GiB-second | 0.154453 | 0.15 |

| Cloud Storage | Standard Storage US Multi-region | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 5.635 | gibibyte month | 0.146461 | 0.15 |

| Cloud Storage | Multi-Region Standard Class B Operations | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | “84,984” | count | 0.033944 | 0.03 |

| Cloud Run | Cloud Run Network Egress via Carrier Peering Network - North America Based | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 1.049 | gibibyte | 0.01781 | 0.02 |

| Cloud Storage | NA-based Storage egress via peered/interconnect network | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 0.231 | gibibyte | 0.009187 | 0.01 |

| Cloud Storage | Multi-Region Standard Class A Operations | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-29 | 194 | count | 0.00097 | 0 |

| Cloud SQL | Network Internet Egress from Americas to Americas | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 0.005 | gibibyte | 0.000932 | 0 |

| Cloud SQL | Network Internet Egress from Americas to EMEA | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 0.001 | gibibyte | 0.000133 | 0 |

| Cloud SQL | Network Internet Egress from Americas to China | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-30 | 0 | gibibyte | 0.000003 | 0 |

| Cloud SQL | Network Internet Egress from Americas to APAC | Usage | 2022-03-06 | 2022-03-26 | 0 | gibibyte | 0.000002 | 0 |

| Cloud Run | Memory Allocation Time | Usage | 2022-03-06 | 2022-03-31 | 1.75 | GiB-second | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Run | Requests | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | “1,049,960” | Requests | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Run | Cloud Run Network Intra Region Egress | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 2.496 | gibibyte | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Scheduler | Jobs | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 62 | Job-days | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Functions | Invocations | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | “1,011,934” | invocations | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Functions | Network Egress from us-central1 | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 1.549 | gibibyte | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Functions | CPU Time | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 13.06 | GHz-second | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Functions | Memory Time | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 175.525 | gibibyte second | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Logging | Log Volume | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 4.507 | gibibyte | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Build | Build time | Usage | 2022-03-15 | 2022-03-29 | 32.583 | minutes of build time | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Storage | Download Worldwide Destinations (excluding Asia & Australia) | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 0.042 | gibibyte | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Storage | Regional Standard Class B Operations | Usage | 2022-03-15 | 2022-03-29 | 107 | count | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Storage | Standard Storage US Regional | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 0.099 | gibibyte month | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud SQL | Network Google Egress from Americas to Americas | Usage | 2022-02-28 | 2022-03-31 | 5.633 | gibibyte | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Pub/Sub | Message Delivery Basic | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 0.003 | tebibyte | 0 | 0 |

| Cloud Pub/Sub | Intra-region data delivery | Usage | 2022-03-01 | 2022-03-31 | 1.102 | gibibyte | 0 | 0 |

Conclusion⌗

I knew going into this I could probably hit a hosting target price of about $40, but hitting $27 was just very sweet. This puts the GCP cost at about $100 less than the equivalent AWS hosting. Even with the recent changes to pricing that everybody seemed to freak out about, to the best of my ability, I think this would raise my cost by maybe $5/month in the worst circumstances?

I’m quite happy with the level of service quality I get, I feel confident in the application I’ve deployed, and I can easily pay for it without even having to let my spouse know ahead of time. I think GCP will be the platform I opt for going forward.